Part 4 - Improving Performance with Asynchronous Messaging

Modernizing apps can be a significant amount of work. You can break a monolithic app into microservices along the lines of bounded contexts, re-platform all the services to use .NET Core and run them in Nano Server containers. There’s a lot to gain from doing that, and the Docker platform enables that approach, but it’s a rebuild project which needs a lot of investment. Docker also supports a more targeted, feature-driven modernization, where you take specific features of your app that need improving, and redesign them to take advantage of Docker - without an extensive rebuild.

You’re going to look at one feature improvement in this part, addressing performance and scalability. In version 1 of the app the sign-up form makes a connection to the database and executes synchronous database queries. That approach doesn’t scale. If there’s a spike in traffic to our site you can run more web containers to spread the load, but you’d hit a bottleneck on the number of open connections the database can handle. You’d have to scale the database too, because the web tier is tightly coupled to the data tier.

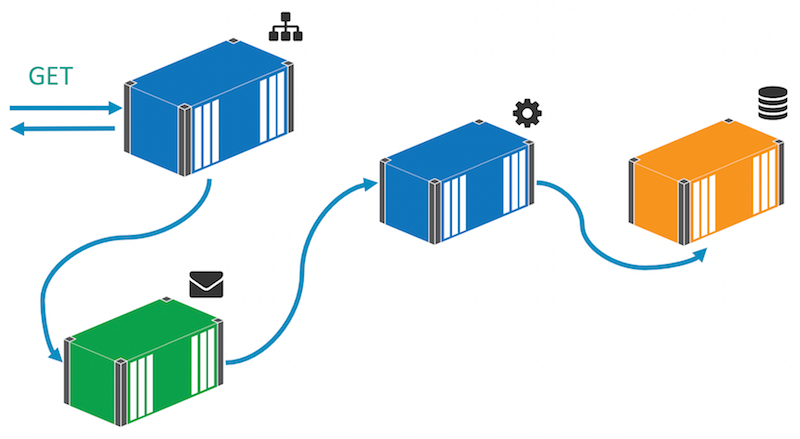

For this scenario, you can easily address that by making the sign up feature asynchronous. Instead of persisting to the database directly, the sign-up form will publish an event to a message queue, and a handler listening to that event makes the database call:

That decouples the web layer from the data layer and means you can scale to meet demand just by adding more web containers. At times of high load the message queue will hold onto the events until the handler is ready to action them. There may be a delay between users clicking the button and their data being persisted, but the delay is happening offline - the user will see the thank-you page almost instantly, no matter how much traffic is hitting the site.

Changing the App to Use Asynchronous Messaging

In the v2-src folder there’s a new version of the solution which uses messaging to publish an event when a prospect signs up, rather than writing to the database directly. The main change is in the SignUp code-behind for the webform. In version 1 the btnGo_Click handler used this code, to insert the prospect details into the database:

using (var context = new ProductLaunchContext())

{

//reload child objects:

prospect.Country = context.Countries.Single(x => x.CountryCode == prospect.Country.CountryCode);

prospect.Role = context.Roles.Single(x => x.RoleCode == prospect.Role.RoleCode);

context.Prospects.Add(prospect);

context.SaveChanges();

}

In version 2, that’s been replaced with this code to publish an event message:

var eventMessage = new ProspectSignedUpEvent

{

Prospect = prospect,

SignedUpAt = DateTime.UtcNow

};

MessageQueue.Publish(eventMessage);

The ProspectSignedUpEvent object contains the original Prospect object, populated from the webform input. The MessageQueue class is just a wrapper to abstract the type of message queue. In this lab you’ll be using NATS, a high-performance, low-latency, cross-platform and open-source message server. NATS is available as an official image on Docker Store, which means it’s a curated image that you can rely on for quality. Publishing a Message to NATS means multiple subscribers can listen for the event, and you start to bring event-driven architecture into the application - just for the one feature that needs it, without a full rewrite.

Changing App Configuration to use Environment Variables

One other thing has changed in the WebForms app. Instead of using Web.config for configuration values which may change between environments, the app now uses environment variables. Lightweight modern app frameworks like NodeJS and .NET Core use environment variables for configuration settings, because they’re available in pretty much any host platform - Windows, Linux and PaaS platforms in the cloud. You can do the same in full .NET apps, and moving from config files baked into the deployment package to environment variables set by the platform makes your app more portable.

In the Entity Framework ProductLaunchContext class the database connection string is now loaded from an environment variable, using a simple Config class which just reads the value by its key:

var value = Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable(variable, EnvironmentVariableTarget.Machine);

To configure the database, you need to set the connection string as an environment variable named DB_CONNECTION_STRING. A similar Config class in the message queue project gets the URL for the NATS host from an environment variable named MESSAGE_QUEUE_URL. The Docker platform has first-class support for environment variables. They can be created with a default value in a Docker image, and containers can be run with specific values.

In the Dockerfile for the web app, the default value for the message queue URL is specified as an environment variable using the ENV instruction:

ENV MESSAGE_QUEUE_URL="nats://message-queue:4222"

Any container you start from that image will have the same value for the URL, unless you specifically override it. For the message queue, that’s what you want because you’ll control the name of the message queue container and you can be confident it will always match the expected URL. For the database connection string there isn’t a default value, because it needs user crtdentials which are likely to change between environments, so you will specify that at the container level.

Building a .NET Message handler

Now the web app is built and configured to use messaging, you need another component in the solution to listen for events and save data to the database. Message handlers are typically simple components that do a single job - they listen for a specific type of message and act on it.

In the version 2 source folder there’s a message hanbdler project. It’s a .NET console app with all the code in the Program class. It connects to NATS using the same messaging project, and listens for ProspectSignedUpEvent messages. For each message it receives, the handler extracts the prospect details from the message and saves them to the database:

var prospect = eventMessage.Prospect;

using (var context = new ProductLaunchContext())

{

//reload child objects:

prospect.Country = context.Countries.Single(x => x.CountryCode == prospect.Country.CountryCode);

prospect.Role = context.Roles.Single(x => x.RoleCode == prospect.Role.RoleCode);

context.Prospects.Add(prospect);

context.SaveChanges();

}

That’s the exact same code that was in the web form in version 1. This is a common pattern that applies for any features which are resource-bound and need to scale well. You extract the functionality from the synchronous implementation, and publish a message instead. Then you move the extracted code to a message handler - this is a simple example, but if you have a complex function with multiple external dependencies, the practice is exactly the same.

In this case you’ll be running a single instance of the message handler, but for performance-critical functions you can run multiple instances and they will share the work from the queue. The message queue acts as a buffer, smoothing out any peaks in demand from the website and presenting a consistent flow of work to the message handler.

The messaga handler will run in a Docker container too. The Dockerfile is very simple. .NET is already installed in the microsoft/windowsservercore base image, so the Dockerfile just configures the DNS cache, sets the default message queue URL in an environment variable and copies in the compiled console app. In this example there’s no HEALTHCHECK, but it would be good practice to add an HTTP endpoint to the console app which reported the app status, so you could add a health check to this component.

Co-ordinating Multiple Containers in Docker

The application has evolved in version 2, and you now have a distributed solution running across four containers. There are dependencies between those containers. The database and the message queue need to be running for the web application to run correctly, and the message handler needs to be running for the full feature set to work. The containers all need to be on the same Docker network so they can communicate, and the dependent containers need to have the expected names so Docker can resolve them by hostname.

You could manage those dependencies manually by starting containers in the correct order, or you could automate all the docker run commands in a PowerShell script. A better option is to use another part of the Docker Platform, Docker Compose. Compose is a tool for capturing complex distributed solutions in a single, executable script file. Just as the Dockerfile replaces the deployment document for a single component, the compose file replaces the deployment document for a whole solution.

This is the definition of the web application in the version 2 Docker Compose file:

product-launch-web:

image: modernize-aspnet-web:v2

ports:

- "80:80"

environment:

- DB_CONNECTION_STRING=Server=product-launch-db;Database=ProductLaunch;User Id=sa;Password=d0ck3r_Labs!;

depends_on:

- product-launch-db

- message-queue

networks:

- app-net

Docker Compose lets you capture the setup of each service using familiar terminology from docker run. You specify the image to create containers from, publish port 80, and set up the database connection string in an environment variable (if you think having the credentials in plain text isn’t good, there are other ways of dealing with secrets in Docker.

There is extra functionality in Docker Compose too. The depends_on attribute lets you explicitly define dependencies between services. In this case the web service is dependent on the database and message queue services - Compose will ensure those services are running before it starts the web service (“service” is Compose terminology - a service definition is implemented by running one or more containers).

In the version 2 code, the compilation build script adds a new step to build the message handler console app. The ASP.NET build agent we put together in Part 1 can also build the console app, so the packaging build script uses the same build agent for the website and the console app. There’s a new docker build step to create the image for the console app, and that’s all you need to build and package the full solution.

Running the Version 2 App with Docker Compose

You should clean up the previous version of the app by killing and then removing all the containers. WARNING: this will remove all of your containers.

docker kill $(docker ps -a -q)

docker rm $(docker ps -a -q)

Docker Compose can be used for running solutions as well as defining them. From the v2-src directory you can build and run the application with two commands:

.\build.ps1

docker-compose up -d

If you’re using Docker for Windows on Windows 10, then Docker Compose is already installed as part of the package. On Windows Server 2016 you can download

docker-compose.exefrom the GitHub release page.

Under the hood, Docker Compose uses the API from the Docker Engine to run containers. It’s a wrapper around the Docker Engine rather than a separate component. When you run this for the first time, Docker will pull down the NATS image (which is a very small layer on top of the Windows Server Core image), and then start all the containers. docker ps will show you all the containers, and you can fetch the IP address of the new web container with:

docker inspect --format '' v2src_product-launch-web_1

Now you can browse to the website and enter a new prospect, and the behavior for the user is exactly the same. But the web layer and data layer are decoupled, so to support thousands of concurrent users, you can scale up just by running more containers on more hosts in a Docker Swarm.

To verify that the event message is being published and handled, you can look at the logs from the message handler running in the .NET console app:

> docker logs v2src_save-prospect-handler_1

Connecting to message queue url: nats://message-queue:4222

Listening on subject: events.prospect.signedup

Received message, subject: events.prospect.signedup

Saving new prospect, signed up at: 2/1/2017 8:48:34 PM; event ID: f11fba28-45ee-4476-a9a8-24b3c4689240

Prospect saved. Prospect ID: 1; event ID: f11fba28-45ee-4476-a9a8-24b3c4689240

That output is from the Console.WriteLine() statements in the code, which Docker is able to record and show. And you can still run a SQL command in the database container:

docker exec v2src_product-launch-db_1 `

powershell -Command `

"Invoke-SqlCmd -Query 'SELECT * FROM Prospects' -Database ProductLaunch"

That will return any data you added since you started version 2:

ProspectId : 1

FirstName : Gordon

LastName : Turtle

CompanyName : Docker, Inc.

EmailAddress : gordon.the.turtle@docker.com

Role_RoleCode : DM

Country_CountryCode : USA

If you’re wondering where all the data went from testing version 1 of the app, in version 2 you’re running a completely new container. In this lab you’re not using Docker Volumes to persist data outside of the container, but take a look at the SQL Server Lab to see how to do that.

Part 4 - Recap

Moving the web app to Docker gives you a modern, scalable and easily pluggable platform to modernize it. Containers running in the same Docker network can communicate with very little overhead, and with Docker Store there are thousands of ready-built, enterprise-grade, open-source applications which you can drop straight into your solution.

You made one of the app features asynchronous by pulling the functionality out of the website, and into a message handler, using the NATS message queue to plumb them together. NATS is a very performant, high-quality messaging system which is perfect for microservice or event-driven architectures, and it can be added to a Dockerized solution with very little effort. Without Docker you would need to commission servers for the message queue and ensure it ran with the same level of high-availability as the web application. With Docker you run the queue and the app on the same cluster, and the whole solution has the same level of HA.

Performance problems are a great candidate for taking into a modernization program. With asynchronous messaging you can add scalability and performance by targeting a specific feature. In the last part of the lab, you’ll see that the Docker platform makes it just as easy to spin out existing features into new containers, but maintain synchronous communication - in Part 5 - Enabling fast prototyping with separate UI components.